Audiencia

FICTION

BY

MONIQUE QUINTANA

You see, Rae could not sew, even if she wanted to very badly. Every night she stayed up late, rummaging through her grandmother’s dress patterns, trying to find one that her hands could actually sew. Her grandmother had closet-upon-closet stuffed with clothes. Dresses with flowers and plaid shirts with silver buttons, hook and eye buttons, shoes that smelled like they used to be brown.

Once she pulled out all the wooden baskets from the closet and exhausted herself, laying herself flat on the carpet, imaging herself an angel. She had spools of thread everywhere, needles everywhere that she lost in the carpet like insects. She ran her fingers through the carpet trying to find them, and gave up, decided that she’d have a siesta right there. She had enough time to do that before anyone called her for dinner. Just then, as birds began to tap incessantly on the window, did the accordion doors of the closet burst open on their own. She jumped up and ran out, the thread catching in her toes. She ran down the stairs, not even taking the time to slide down the bannister like she usually did. She found her family at the bottom, her family smoked out in the living room, grandfather’s cowboy boots, and the sparkle of a mustache. She felt a dull ache in the her feet. You’re walking like a ballerina, they told her. Look at how your feet are bleeding.

Rae truly believed that her grandfather didn’t love her as much as he loved his other grandchildren. One day she even found herself trying to make herself care that her grandfather didn’t love her, but she didn’t. Rae’s grandfather was born in Texas under a moon the color of paste. It was Rae that imagined it this way, as she crafted in the warm glow of the kitchen, the paste in its red plastic pot, her fingers digging in the pot and thumping paste buttons onto sheets of construction paper. She wondered why it was even called construction paper. Her family was in construction. They built big houses. These papers could build only weak houses stuck together with paste. She decided to make a little house with the construction paper. A diorama in a show box with a tarantula head poking out of the window. Good tarantula legs sprawled out on a chair made of ice lolly sticks, each of its’ legs stemmed inside a cowboy boot, the same color brown as her grandfather’s.

That night, the night the big idea came, Rae tried to pronounce her grandfather’s name in a Mexican kind of way. She lay on the sofa, with her toes sticking out from a itchy red blanket. She hated the ways her toes looked and wished they were pale like her cousin Cassandra’s, who had pretty pink nails dotted with daisies. But Cassandra couldn’t keep a real flower alive and that made her feel both joyful and wicked.

She decided to get back to thinking about how to be a better Mexican or even a better granddaughter of a Texan. She tried to imagine her grandfather as a little boy, polishing shoes until they were clean like chicken bones in a pot. She’d never forget the night that her grandfather bursted from his saloon, whiskey bottle at his hip, and declared that he had the answer to all of their money problems. Rae wondered if her family would ever be cured of bursting through doors. She decided that bursting through doors must have been some kind of ailment that her family was inflicted with. She also decided that her grandfather was a happy drunk because he was pretty mean when he wasn’t drinking. Mas chingón was what her cousin Cassandra had said. Have you ever seen how mad he gets when he loses his mustache scissors? He has the fury of one thousand cowboys riding against the sunset.

There was no sunset for her grandfather to ride on, just the blood rains tainting his boots to a color that he didn’t like. Nothing could be simpler, he said. We need to give everyone something fun to do. In this rain season, they wouldn’t pay him to build a house, but they would pay to see ours, to come inside, to have some fun there. The truth, as he believed it, was that everyone in town wanted to know what the inside of their house looked like. Entry into the house was usually reserved for friends and out of town relatives. Rae knew that she wasn’t one of her father’s favorite grandchildren, so she was wary of bringing guests to the house, but her boy cousins would bring them over occasionally and they would spend most of the time in her grandfather’s saloon, playing pool and talking about how the old brandy on the counter tasted just like cherry cough syrup and made them horny for girls. It didn’t help much that her grandfather had papered the walls of the saloon with pale women smoking cigars, wearing draped gowns, their nipples peeping out the top of their gowns like cherries. Each time Rae saw one of the boys walk up to caress the women there, she would make a sucker sound with their mouth and the boy would retreat and she would laugh behind her hand, very pleased to make the boy yo-yo back to the pool table, only half the dream of that place realized. It was one way she kept the house completely in her family. She knew that if the boys touched too much of their house, part of them would be there, and this was how she knew that she really was loyal after all.

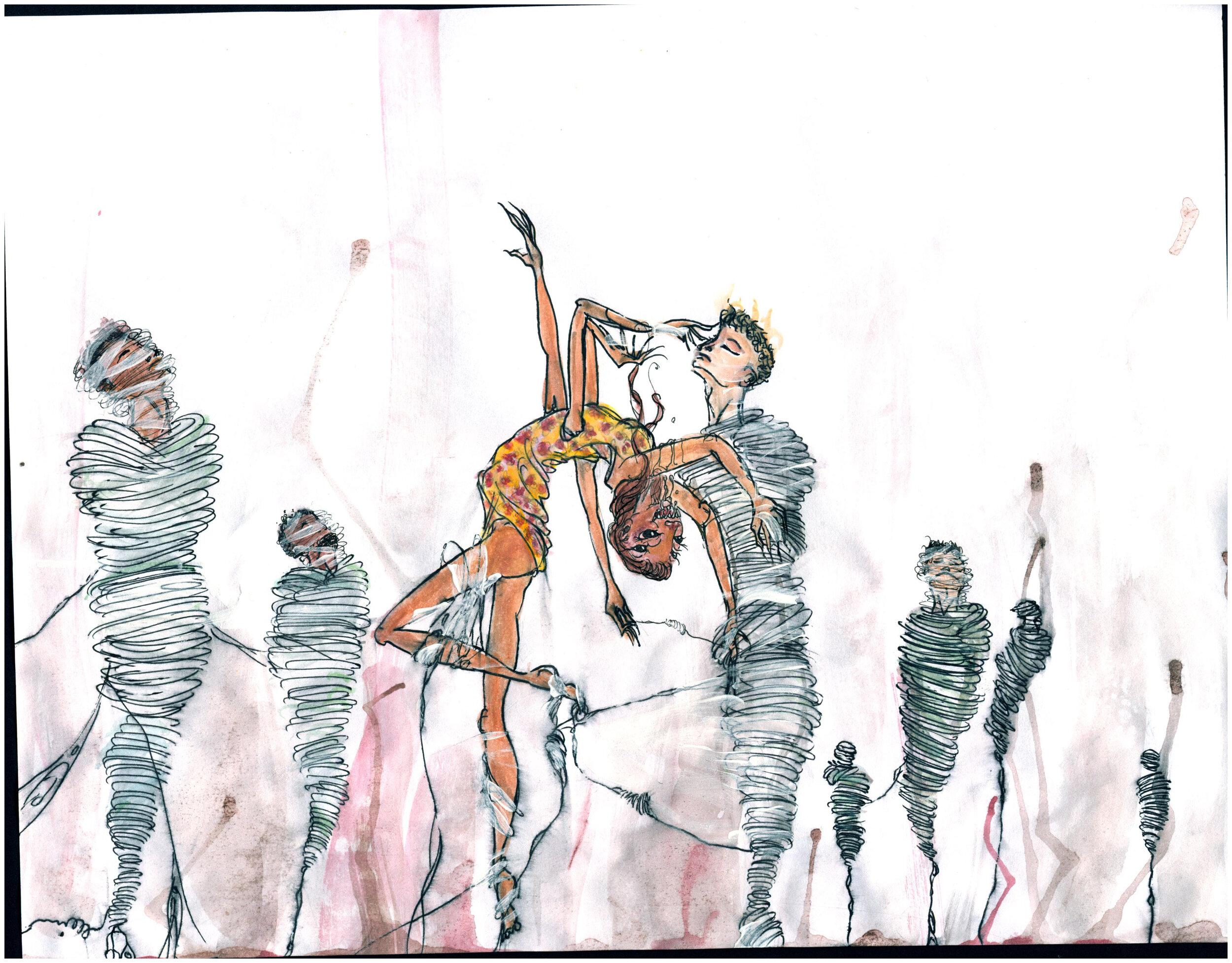

ART BY ELIZABETH BOLAÑOS

Rae didn’t think much for most of those boys, except for one whose name she could never remember, but who had dark brown eyes and hair the color of what she thought the taste of cinnamon was supposed to taste like. He had been swinging on one of the barstools and fell over on his back. He moaned for a few minutes, finishing the last of his Shirley Temple drink, and click clacked his way out of the saloon. Afraid she’d catch her watching him, Rae began to roll her way behind a potted sago plant, but she was caught mid roll, and there he was, cinnamon head, smiling at her, smelling like a soap forest. He pulled her up with one arm and pulled her dress down over her thighs. Is that a caterpillar on there? He laughed, his arm dangling.

Rae realized that he wasn’t as good looking close up, but she appreciated that he noticed the caterpillar print on her dress because she had spent her whole week’s allowance of the fabric. It glows in the dark, she told him, walking him to the front door. The stained glass windows burned bright orange there. She opened the door for him, string bean thing that you are, she thought to herself, and there was a blonde girl on the other side, pleated skirt down to her ankles. Tell your grandpa Hank, thanks so much for having us over, the cinnamon boy said, bending down and kissing her on the cheek. Hey honey, he said to the blonde girl, her skirt sprinkled with rain and dust, flapping in the cool wind. The eyes of her looked at the eyes of Rae, and she laughed in spite of herself. So much had happened and it wasn’t even noon yet. That skirt, she thought, that girl’s skirt. That girl wants to kill me.

Grandpa Hank was the most stubborn man in town and the most stubborn man in the family and because of that, he could be the only one to write the ballet play. The play, he said, would be something that he heard as a boy. The play would make a sublime beauty out of a Mexican tragedy. A woman who was asked to sign away her truest loves. It would be about Grandpa Hank’s favorite heroine, Sor Juana ines de la Cruz, the ravishing beauty that was a poeta, who at the end of her youth, when she had gone from a bright flower to the brightest flower, gave up all her fine telescopes to the church, who did God knows what with them, and who gave up writing plays and poems and convictions of mere mortal men for her God. She lived a long life with many things they could talk about, but the part of the shaking beauty that was her life, the moment that she was tested by men who would never deserve her, that would be in their play. The day it was demanded that she prove her intelligence before an audience of men.

Audiencia. It was a word that Rae heard in school, in her Mexican history class, which her her grandfather insisted she sign up for. On bright sunny Saturday mornings, she sat through the booming lectures of her profe, a man she found both frightening and delightful. She sat in the front of class, so that her profe wouldn’t know she was afraid of him. Going to that class felt good to her and she learned more about her people. The audiencia. It meant something else in school, but the fact that the word came from school gave her grandfather’s ballet the ring of distinction that it needed.

He likened the play to the inside of a pomegranate. Cut it open and you could see all the seeds of it. All the men were the seeds, but Juana was the beauty that surpassed the seeds, the thing that looked like membrane, the thing that made everything hold together inside the fruit. Men were really afraid of women, he said. Rae knew that he was afraid of her grandmother, even if he had played it off when she was alive.

Why couldn’t it be a just a dramatic play? Why did it have to be a ballet? Rae asked as he raked out the ash from the fireplace. She held a paper bag open for him while he did this, and she knew that the black soot was making a mask on her face. She wiped half the mask off and saw it looked like the smile on her sleeve. Why a ballet? She imagined kid legs twisting on the floor, the ribbons choking ankles, the soot from the fireplace making their toes like chalk on the floor. Her grandfather told her it was because the town needed to get its grace back. There had been grace once, when everyone missed each other, when they longed for each other, when they would leave their homes freely, then return home at night, when their dogs growled at their boots for lack of affection. Yes, that was true. Not even the dogs were getting the kind of attention they had been used to, they’re fevered paws and glassy eyes like tequila shots. At night, they howled up to the warm pink sky, like it was the only thing that would ever really love them.

GET CENOTE CITY BY MONIQUE QUINTANA

Monique Quintana

Xicana writer and the author of the novella, Cenote City (Clash Books, 2019). She is an Associate Editor at Luna Luna Magazine and Fiction Editor at Five 2 One Magazine. She has received fellowships from The Community of Writers at Squaw Valley, The Sundress Academy of the Arts,and Amplify. She has also been nominated for Best of the Net and Best Micofiction 2020. Her work has appeared in Queen Mob’s Tea House, Winter Tangerine, Grimoire, Dream Pop, Bordersenses, and Acentos Review, among others. You can find her at [www.moniquequintana.com]

Elizabeth Bolaños

Xicanx dipped strawberry and identical twin. She is a student in Fresno State’s MFA Program in Creative Writing with an emphasis in fiction, a journalist at La Voz de Aztlan and an intern at The Normal School. Her writing and interviews have appeared in Flies, Cockroaches, and Poets and The San Joaquin Review Online.